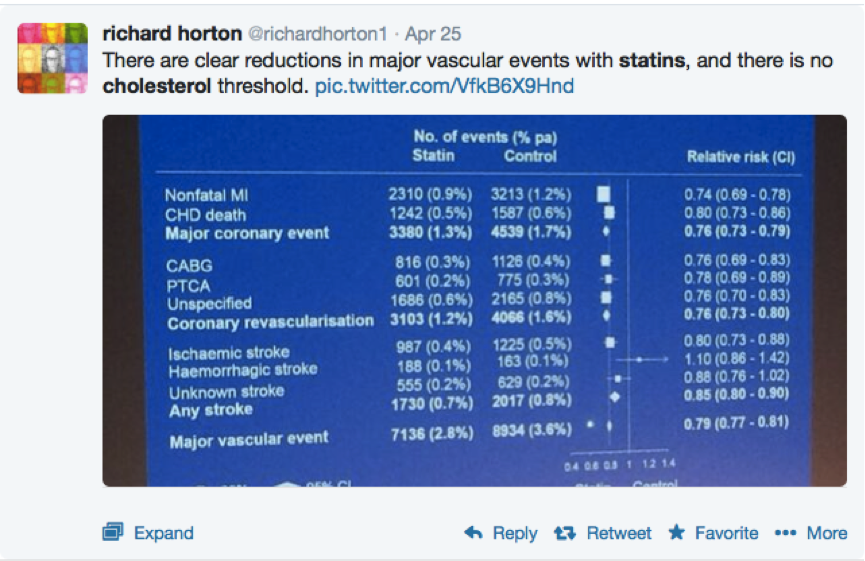

This week, I noticed a tweet from the editor of the medical journal The Lancet, Richard Horton (screenshot below).

The attached image seems to be a photograph of a slide from a presentation. The data comes from a review of the evidence regarding the impact of statins on health outcomes from 2010 [1]. This study amassed evidence from 26 individual statin studies. The bottom line of the slide pictured tells us that statin therapy reduced ‘Major vascular event[s]’ by 21 per cent.

Richard Horton seems very taken with the results (perhaps this has something to do with the fact that the study was published in his journal). However, there are a few things about the review that I think are perhaps worth bearing in mind.

Its authors (from the Cholesterol Treatment Triallists collaboration) essentially concluded from their data that more intensive statin therapy produced better outcomes. They extrapolated their findings to conclude that if LDL-cholesterol were to be reduced by 2-3 mmol/l, then risk would fall by 40-50 per cent.

Are these conclusions founded in good science?

Firstly, the ’40-50 per cent reduction’ claim is an extrapolation. It’s not based on actual data, just on a projection the authors make from existing data. In other words, it’s not very scientific at all.

But also, statin drugs have a number of different mechanisms (including an anti-inflammatory effect) that might allow them to reduce cardiovascular disease risk in ways that have nothing to do with cholesterol reduction. Now, when we intensively lower cholesterol with statins, non-cholesterol-related effects (e.g. anti-inflammatory action) will generally be increased too. The bottom line is we cannot assume that any additional benefits from more intensive statin therapy come from more intensive lowering of cholesterol per se.

In this ‘meta-analysis’, the results of a large number of studies was pooled. The problem is, these studies used a range of different drugs at different doses. Sometimes, the drugs were being tested against placebos, and sometimes they were being tested against other drugs. A more scientific way of determining if higher doses of statins really are better is simply to compare the effects of two doses of the same statin. You’d be surprised how rarely such studies are done.

One such example, though, is the so-called TNT study [2]. Here, individuals with heart disease (very high risk of future vascular events) were given either 10 or 80 mg of atorvastatin for an average of about 5 years. The higher dose did lead to lower LDL levels and lower risk of death due to heart disease. The absolute reduction in risk was 0.5 per cent, by the way, which meansrisk of dying from heart disease fell by about 0.1 per cent per year (so nothing to get too excited about).

Also, the higher dose of statins (a full 8 times the lower dose) did not lead to a reduction in overall risk of death. In other words, taking 8 times the lower dose of atorvastatin did not extend life by a single day.

The idea that the anti-inflammatory effects of statins (and not their cholesterol-reducing effects) may be at the heart of their benefits has been bolstered by work focusing on an inflammatory marker known as C-reactive protein (CRP). Statins are known to have the capacity to reduce CRP levels.

In one study assessing the relationship between statin therapy and cholesterol and CRP levels, it was discovered that “Patients who have low CRP levels after statin therapy have better clinical outcomes than those with higher CRP levels, regardless of the resultant level of LDL cholesterol.” [3] (emphasis mine).

In another study, statin therapy and cardiovascular disease risk assessed using ultrasound scanning of the inside of the coronary arteries [4]. It was found that “atherosclerosis regressed in the patients with the greatest reduction in CRP levels, but not in those with the greatest reduction in LDL cholesterol levels.”

So, despite what the authors of the Lancet review would have us believe, there is evidence that statins primarily work through mechanisms that are independent of their cholesterol-reducing effects.

But, I’d also like to focus a little on other findings from this review, specifically the impact of statins on overall mortality. First of all, it’s worth bearing in mind that for people who do not have a history of heart attacks or strokes (so-called ‘primary prevention’) statins do not reduce the risk of death overall.

They do appear to reduce the risk of death in those with a history of cardiovascular disease (so-called ‘secondary prevention’). In the Lancet review, overall risk of death was found to be reduced by 10 per cent (a result that was statistically significant). However, this relative risk reduction needs to be taken in the context of overall risk. It turns out, that over the course of a year, risk of dying was reduced from 2.3 per cent to 2.1 per cent. In other words, the absolute risk reduction per year was 0.2 per cent – not exactly earth-shattering.

There’s another measure that is useful in gauging the effectiveness of a treatment: the ‘number needed to treat’ or ‘NNT’. We can use the data to calculate, for example, the number of people needed to be treated with statins for a year to prevent one death. The answer is 500. The NNT for deaths due to cardiovascular disease is even higher: 1,000.

Bearing in mind the relatively high risk of serious side-effects (the best estimates comes in at around 20 per cent), one would have to wonder on what the enthusiasm many doctors, researchers and medical journal editors have for statins is really based. Only they can possibly know.

References:

1. Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet 9 November 2010 [epub ahead of print]

2. La Rosa JC, et al. Intensive lipid lowering with atorvastatin in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(14):1425-35

3. Ridker PM, et al. C-reactive protein levels and outcomes after statin therapy. N Engl J Med 2005;352(1):20-8

4. Nissen SE, et al. Statin therapy, LDL cholesterol, C-reactive protein and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(1):29-38