NHS Choices website purports to give the general public information and advice about a wide range of health matters. My impression is that many see the NHS Choices website as a portal for honest, trustworthy and balanced health advice.

A couple of weeks back, I noticed that Paul Nuki, Editor of NHS Choices, had tweeted a link to an NHS Choices infographic about the hazards of salt in the diet. On following the link, I found myself being informed that if the UK public were to reduce salt consumption by 1 g a day, this would save 4,147 lives each year as a result of a reduced risk of cardiovascular events such as heart attack and stroke.

I do like to check the sources of these sorts of claims wherever possible, but the reference for this claim simply read ‘Department of Health’. This is not a reference. This is really no better than me listing as a reference ‘My Uncle Harry’. If one is going to make a claim such as this, then it is incumbent upon NHS Choices to provide the actual evidence on which it is based.

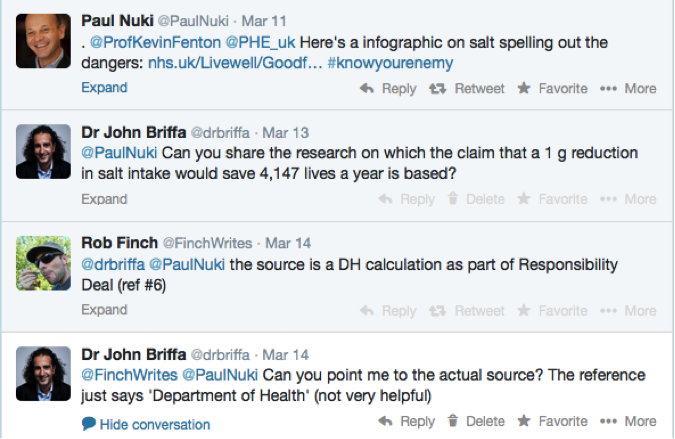

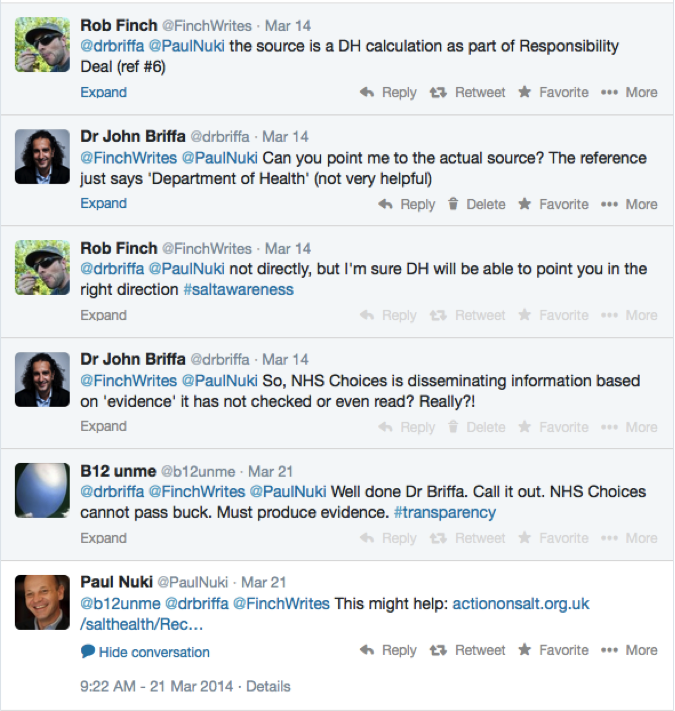

I asked Paul Nuki for the evidence. His colleague, Rob Finch, replied, and you can see our exchange here.

Please note that Rob Finch fobbed me off by referring me to the Department of Health. No reference was supplied, and somehow I think Rob Finch’s glib manner signalled that he thought this was perfectly acceptable behaviour. I didn’t, which provoked my comment about NHS Choices appearing to be happy to support its assertions by quoting evidence it seemed to be utterly unfamiliar with.

A full week later, Paul Nuki finally came back to me with a link to this study [1]. Dating from 2003, this piece of research summarises the evidence regarding the blood pressure reductions that come from salt restriction in the diet. The first thing that occurred to me is that this piece of research had, seemingly, nothing to do with the Department of Health reference cited in the infographic.

But, can the quoted study even be used to justify the claim about lives saved?

The research is actually based on studies that assessed the impact of salt restriction on blood pressure. The authors have then extrapolated the modest reductions seen in blood pressure to reductions in deaths due to strokes and heart disease.

Nowhere in the paper are there any calculations based on reductions in salt consumption of 1 g per day (the specific salt reduction quoted in the infographic). Also, nowhere in the paper do the authors explain how they calculated reductions in blood pressure to reductions in deaths. Critically, at no point do they explain why we cannot be assured that reductions in blood pressure will translate into health benefits. The authors have, in fact, made a huge assumption here.

If we want to know if salt restriction saves lives, then we require studies that assess the impact this intervention has on ‘hard clinical endpoints’ like deaths from heart attacks, and overall risk of death (overall mortality).

Do we have such data? Yes, we do, and the relevant evidence has been summarised by researchers from the Cochrane Collaboration (whose self-appointed job it is to do proper reviews of the evidence concerning clinical endpoints). The last time Cochrane researchers reviewed the evidence was in 2013 [2], though this review was subsequently withdrawn when they became doubtful about the trustworthiness of some data they had used which suggested that salt restriction might actually increase the risk of death in those suffering from heart failure.

Prior to that, the most recent review conducted by the Cochrane researchers was published in 2011 [3]. The reviewers assessed studies which included people with normal blood pressure (normotensives), people with high blood pressure(hypertensives),or both. Here’s the impact salt restriction had once the results of relevant studies were pooled together:

1. Normotensives

No reduction in risk of stroke and heart attack

No reduced risk of death overall

2. Hypertensives

No reduction in risk of stroke and heart attack

No reduced risk of death overall

And this was despite salt reduction in these studies was generally greater than the 1 g reduction quoted in the NHS Choices infographic. According to this evidence, the number of lives saved by an average 1 g reduction in salt intake per day would be precisely none.

Let me list NHS Choices’ misdeeds as I see them:

1. Stating that lives would be saved from modest salt intake reduction and not quoting a proper reference to support this scientifically

2. Glibly fobbing me off when asked for the evidence

3. Taking a week to come back to me eventually, but with a piece of research that had no direct relationship to the quoted ‘evidence’

4. Relying on evidence of the impact of salt reduction on a so-called ‘surrogate marker’, rather than proper, clinical endpoints such as risk of heart attack or risk of death

In don’t take Rob Finch’s dismissal of my request personally, but I do feel it smacks of arrogance and a lack of professionalism. But, for me, worse than that is the fact that NHS Choices seems happy to quote evidence that it seems to have dragged out of nowhere, especially when I’d say it is soundly trumped by evidence that focuses on all-important clinical endpoints.

As I stated at the top of this piece, I think many people look to NHS Choices for trustworthy advice, and believe what this body says. NHS Choices has a duty, I think, to fulfil its brief properly, and I believe in this instance it has failed to do so.

If NHS Choices would like to be seen as a credible source of health information, then I believe it needs to up its game considerably. Until that time, those keen on getting the facts may choose to give NHS Choices a miss, and seek their health advice elsewhere.

References:

1. He FJ, et al. How Far Should Salt Intake Be Reduced? Hypertension 2003;42:1093-1099

2. Taylor RS, et al. Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease 2013 DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009217.pub2

3. Taylor RS, et al. Reduced dietary salt for the prevention of cardiovascular disease 2011 DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD009217