Some nice person sent me a link to this article earlier this week which appears in the UK’s broadsheet newspaper The Telegraph. I mention the fact that this publication is a ‘broadsheet’ because these larger format newspapers generally have a reputation of higher quality reporting compared to the ‘tabloids’.

Whether that true or not, I don’t know. What I do know is that the ‘story’ here is a familiar one. It actually appears to be about some research which links higher saturated fat with speedier mental decline during ageing, and monounsaturated fat with a protective effect. But the real story here, for me at least, is about how the reporter, Stephen Adams, at no point mentions that fact that this is an epidemiological study, and the limitations of this sort of research.

In short, epidemiological studies look at associations between things. However, just because one thing is associated with another, this doesn’t mean this one thing is causing the other. This is because of things called confounding factors – perhaps true causative factors that are associated with other factors that are ‘innocent bystanders’. For example, let’s saywe have research which links ownership of a television with an increased risk of heart disease. Do televisions cause heart disease? Probably not. It’s more likely that one of the real issues here is watching television (i.e. sedentary behaviour) which, of course, is associated with owning a television. Eating rubbish snack foods in front of the TV might be a contributing factor here too, of course.

So, getting back to the study reported in The Telegraph, what it showed is that saturated fat is associated with enhanced mental decline. However, let’s all remember that for the last 30-odd years saturated fat has been roundly demonised by the nutritional and medical establishment. At the same time, we’ve heard generally positive things about monounsaturated fat. Now imagine we have a generally health-conscious individual hearing this advice loudly and consistently. Chances are they’ll attempt to act on this advice by cutting back on saturated fat and boosting their monounsaturated fat at the same time. Out goes the eggs and beef and in comes the olive oil and avocado. But, remember, this is a health-conscious type of person, so there’s a good chance they’re not going to smoke, or drink too much, and may well be regularly active too.

On the other hand, someone who is, say, less concerned about their health and has antibodies to health advice might choose to ignore advice to cut back on saturated fat and load up on monounsaturated instead, and may also continue to spend more time in front of the TV, drinking, smoking and eating unhealthy snack foods.

So, how do we know if the mental changes were caused by different dietary fat levels or other factor? We don’t. In an attempt to take account of other relevant factors, researchers can ‘control for’ confounding factors in their analyses. The researchers involved in the fat/brain function study did this, but this practice is essentially a very imprecise science: At the end we still end up with data that really doesn’t tell us anything at all. That’s just how epidemiology is, I’m afraid: correlation does not prove causation.

Now, as I say, Stephen Adams does not mention this major deficiency of epidemiological evidence, and his short story there gives, I think, the unwary reader with the impression that the findings are much stronger than they are in reality.

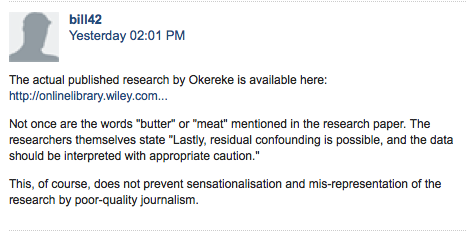

Not so long ago, this would perhaps go relatively unnoticed and unremarked upon. But these days, it appears there are growing numbers of people who are well versed in the scientific method, and who don’t mind pointing out the error of someone else’s ways. Many newspapers now allow readers to make comments. I thought I’d take a few moments to read the comments after Mr Adams’ piece. I was pleased to find that at least some commenters pointed out, fairly and squarely, the limitations of epidemiological evidence. Here’s one of the comments that neatly summed it up, I think.