If you’re reading this blog post on 5th March 2012, there’s a good chance you came to it as a result of listening to discussion on BBC Radio 4’s programme ‘You and Yours’ about the most appropriate diet for those suffering from diabetes. You can listen to the broadcast here (the item starts about 15 minutes into the show). The UK’s largest diabetes charity – Diabetes UK – advises diabetics to include starchy foods with every meal. I strongly object to this on the grounds that this approach is unscientific, counter-intuitive, and likely to worse blod sugar control and increase the risk of complications. I wrote this article ahead of time, because I know how challenging it can be to get all the most important facts out when time is short. This article is an attempt to get down what I believe to be the salient points, with some references to the science where relevant.

What is diabetes?

Diabetes is a condition characterised by raised levels of sugar (glucose) in the bloodstream. It comes in two main forms:

1. Type 1 diabetes: caused by a failure of the body (actually, the pancreas) to secrete insulin – the chief hormone in the body responsible for keeping blood sugar levels in check. It usually develops in childhood or early adulthood. The condition requires treatment with insulin.

2. Type 2 diabetes: here there is often a lot of insulin in the body, but the problem is the body has become somewhat unresponsive to the effects of this hormone (insulin resistance). Sometimes, type 2 diabetics can have difficulty secreting enough insulin as a result of what is sometimes termed ‘pancreatic exhaustion’. The condition generally develops in adulthood (though it’s increasingly being diagnosed in children). Treatment usually involves lifestyle modification (diet and exercise) and drugs. Some type 2 diabetics go on to require insulin. Type 2 diabetes makes up more than 90 per cent of all cases of diabetes.

What’s the problem with raised levels of sugar in the bloodstream?

When blood sugar levels are raised, there’s increased risk of glucose attaching to and damaging tissues. This can lead to complications such as eye disease and blindness, heart disease, kidney disease and poor circulation and nerve damage in the legs which may lead to amputation.

What does Diabetes UK recommend that diabetic eat?

You can read Diabetes UK’s advice for type 2 diabetics here. Here’s a core piece of advice:

At each meal include starchy carbohydrate foods

Examples include bread, pasta, chapatis, potatoes, yam, noodles, rice and cereals. The amount of carbohydrate you eat is important to control your blood glucose levels. Especially try to include those that are more slowly absorbed (have a lower glycaemic index) as these won’t affect your blood glucose levels as much. Better choices include: pasta, basmati or easy cook rice, grainy breads such as granary, pumpernickel and rye, new potatoes, sweet potato and yam, porridge oats, All-Bran and natural muesli. The high fibre varieties of starchy foods will also help to maintain the health of your digestive system and prevent problems such as constipation.

What’s the problem with this advice?

Starch is made up of chains of sugar (glucose) molecules. When we eat starch we digest it down into sugar and then absorb this sugar into the bloodstream from the gut. While it’s often said that ‘complex carbohydrates’ give a ‘slow, steady’ release of sugar into the bloodstream, this is generally not the case at all. We know this from research in which the tendency for foods to disrupt blood sugar levels has been measured to derive what’s known as its ‘glycaemic index’.

The GI is a quantification of the speed and extent to which a food releases sugar into the bloodstream. The higher a food’s GI, the more disruptive it is to blood sugar levels. In the GI scale, pure glucose is given a value of 100, and then other foods are compared to it.

Table sugar (that some people use on their cereal, add to tea or coffee and use in baking) is made of sucrose, which is half glucose and half fructose. The GI of table sugar is about 65.

Just bear these things in mind when consider that boiled and mashed potato have GIs that averages about 55 and 70 respectively. Wholemeal bread has a GI that averages out at about 70. The GIs of white rice, egg noodles and porridge are about 60, 57 and 70 respectively. We can see from this that many of the foods Diabetes UK recommend for diabetics are about as disruptive for blood sugar as eating sugar itself.

You can read what Diabetes UK has to say about the GI here.

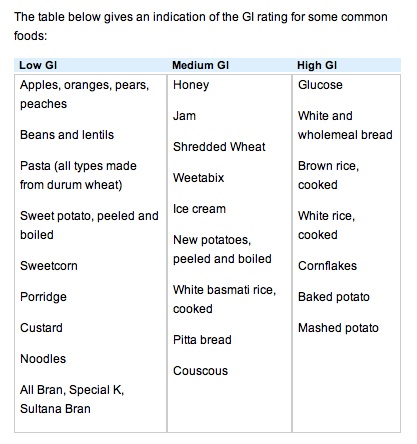

Here you will find that Diabetes UK gives us this table:

Diabetes UK does not define what constitutes ‘low-‘ ‘medium-‘ and ‘high-GI’. However, rather oddly, brown rice gets a ‘high’ rating, though its GI is about 45, while say Shredded Wheat is rated as ‘medium’ while its GI is 83.

Over in the ‘low-GI’ column we have Special K and Sultana Bran, yet both of these cereals have GIs of about 70 (Special K’s GI varies according to country but averages out at about 70). In fact, Diabetes UK gives special mention to these named foods in its breakfast recommendations.

However, including starchy (and sometimes sugary) foods such as these in the diet will likely worsen blood sugar control (compared to a diet lower or devoid of these foods), thereby increasing the need for medication and enhancing risk of complications.

What might explain this misinformation and bad advice?

See here for a list of corporate sponsors of Diabetes UK. In amongst a whole raft of food and diet companies, you’ll see ‘Kelloggs’ (who make Sultana Bran and Special K) and ‘Shredded Wheat’. Could this explain why there highly disruptive foods get special mention from Diabetes UK and make their way into the ‘low-GI’ category even though they are anything but? I don’t know, but we should at least ask the question, I think.

Does eating less carbohydrate help control diabetes?

The evidence regarding lower-carbohydrate eating in diabetes has been well reviewed [1].

This review provided evidence that carbohydrate restriction improves blood sugar control. One study, for instance, found that a low-carbohydrate diet over 6 months allowed more than 95 per cent of type 2 diabetes to reduce or eliminate their medication entirely [2].

It should also be pointed out that, overall, low-carbohydrate diets are significantly more effective than higher carbohydrate, lower-fat diets for weight loss (the evidence is comprehensively reviewed in my latest book Escape the Diet Trap).

Low-carbohydrate eating is not a magic pill, but in practice countless individuals have found it to be highly effective for controlling blood sugar levels and improving markers for disease. I’ve known many type 2 diabetic use this approach to return to a state where tests essentially show no evidence of diabetes.

So what’s wrong with low-carbohydrate diets?

The usual accusation that such diets are high in fat, including ‘saturated’ fat that can cause heart disease (that diabetics are prone to). Actually, there is good evidence that when carbohydrate is cut from the diet, while the percentage of fat increases in the diet, the absolute amount of fat in the diet stays about the same (in other words, those switching to low-carb eating don’t generally eat more fat as a result) [3-6].

This issue is a moot point, because there really is no evidence that saturated fat causes heart disease anyway. There have been several recent major reviews of the evidence regarding role that saturated fat, or fat in general, has in heart disease.

One such review conducted by researchers from McMaster University in Canada found that epidemiological evidence simply does not support a link between saturated fat and heart disease [7]. Another recent study out of Oakland Research Institute in California, USA [8] – this one, a meta-analysis (adding together of several similar studies) found saturated fat consumption has no links with heart disease risk.

Yet another comprehensive review of the relevant literature was performed as part of an ‘Expert Consultation’ held jointly by the World Health Organization (WHO) and Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the US [9]. Again, no association was found between saturated fat and heart disease. This review also included a meta-analysis of intervention studies in which the effects of low-fat diets (these usually target saturated fat specifically) were assessed. Lower fat diets were not found to reduce the risk of either heart attack or risk of death due to heart disease.

The most recent review of the evidence was a 2011 meta-analysis, in which the results of 48 studies were pooled together [10]. Each of these studies tested the effect of reducing fat and/or modifying its nature in the diet. In general, the study subjects reduced saturated fat intake and/or replaced it at least partially with so-called ‘polyunsaturated’ fats (e.g. vegetable oils). The results of this review showed that these interventions did nothing to reduce the risk death due to cardiovascular disease nor overall risk of death. In studies in which lowering and/or modification of fat was the only intervention, risk of cardiovascular events such as heart disease and stroke was not reduced either.

What about fibre?

You’ll notice that part of Diabetes UK’s justification for including sugar-disruptive foods in the diet of diabetics is the fibre they can provide. The sort of fibre that is generally being referred to here is known as ‘insoluble’ fibre – more colloquially referred to as ‘bran’ or ‘roughage’. This is said to provide bulk to our stools, and help prevent constipation and colon cancer.

Actually, insoluble fibre can be irritant to the gut, and provoke symptoms such as bloating and discomfort. On the other hand, the other main form of fibre – ‘soluble’ fibre – tends to improve bowel symptoms such as constipation and abdominal discomfort [11]. Soluble fibre is found abundantly in natural foods such as fruits, vegetables, nuts and seeds.

The idea that insoluble fibre helps prevent colon cancer is not supported by the research, either. For example, studies show supplementing the diet with fibre does not reduce the risk of cancerous tumours or pre-cancerous lesions [12-14].

The authors of a recent review concluded that “…there does not seem to be much use for fiber in colorectal diseases”, adding that their desire was to “emphasize that what we have all been made to believe about fiber needs a second look. We often choose to believe a lie, as a lie repeated often enough by enough people becomes accepted as the truth” [15].

Anything else?

On 2nd March I had an email from someone telling me that he’d recently been approached by people in the street asking for donations to Diabetes UK. Nothing odd about that, except that they, apparently, were using Krispy Kreme doughnuts as an inducement. His enquiries reveal that Diabetes UK sanctions this approach and discourages the elimination of any food group from the diet. What, even doughnuts? What sort of a message does using doughnuts to induce people to donate to Diabetes UK send out? Sadly, in my view, it’s a message that is consistent with the wrong-headed and potentially dangerous dietary advice that this charity dishes out generally.

References:

1. Accurso A, et al. Dietary carbohydrate restriction in type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic syndrome: time for a critical appraisal. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2008 Apr 8;5:9

2. Westman EC, et al. The effect of a low-carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a low-glycemic index diet on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nutrition & Metabolism 2008;5:36

3. Larosa JC, et al. Effects of high-protein, low-carbohydrate dieting on plasma lipoproteins and body weight. J Am Diet Assoc 1980;77(3):264-70

4. Yancy, WS Jr, et al. A low carbohydrate, ketogenic diet versus a low-fat diet to treat obesity and hyperlipidemia. A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med 2004;140:69-77

5. Dansinger ML, et al. Comparison of the Atkins, Ornish, WeightWatchers, and Zone Diets for weight loss and heart disease risk reduction. JAMA 2005; 293: 43–53

6. Gardner CD, et al. Comparison of the Atkins, Zone, Ornish, and LEARN diets for change in weight and related risk factors among over- weight premenopausal women. JAMA 2007; 297: 969–977

7. Mente A, et al. A Systematic Review of the Evidence Supporting a Causal Link Between Dietary Factors and Coronary Heart Disease. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(7):659-669

8. Siri-Tarino PW, et al. Meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies evaluating the association of saturated fat with cardiovascular disease Am J Clin Nutr 2010;91(3):535-46

9. Skeaff CM, et al. Dietary fat and coronary heart disease: summary of evidence from prospective and randomised controlled trials. Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism 2009;55:173-201

10. Hooper L, et al. Reduced or modified dietary fat for preventing cardiovascular disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011 Jul 6;7:CD002137

11. Heizer WD, et al. The role of diet in symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome in adults: a narrative review. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(7):1204-14

12. Fuchs CS, et al. Dietary fiber and the risk of colorectal cancer and adenoma in women. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(3):169-76

13. Jacobs ET, et al. Intake of supplemental and total fiber and risk of colorectal adenoma recurrence in the wheat bran fiber trial. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002 11(9):906-14

14. Alberts DS, et al. Lack of effect of a high-fiber cereal supplement on the recurrence of colorectal adenomas. Phoenix Colon Cancer Prevention Physicians’ Network N Engl J Med. 2000;342(16):1156-62

15. Tan KY, et al. Fiber and colorectal diseases: separating fact from fiction. World J Gastroenterol. 2007;13(31):4161-7

GI references in this blog post values are derived from: Atkinson FS, et al. International tables of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2008. Diabetes Care 2008;31(12):2281-2283